What Are Things For? Lessons from 120 Years of Design for the Age of AI

Reflections from the MUDE Design Museum in Lisbon

The question hangs on the wall in elegant typography: "What are things for?" But as I walked through MUDE's chronological journey from 1900 to 2020, I realized I was seeing more than design history. I was witnessing how each era's deepest anxieties and aspirations crystallize into objects, and getting a preview of how our AI moment will be remembered by future museum visitors.

The exhibition poses even deeper questions: "How do ideas materialise in things and, over time, what influence do they exert? What are the dreams, visions, utopias, or dystopias of the creators of ideas that give rise to things? Do we really need so many things to live our lives? What meaning should be given to new things? Do we even need new things?"

These questions hit me with particular force because I spend my time thinking about software, the most prolific "things" humans now create. The museum's approach reveals "the how and why of things being imagined, planned, drawn, produced, materialised, accepted, perceived and consumed." That sequence matters: before anything else, we imagine. In our AI era, imagination has become the bottleneck, not execution.

The Power of Imagination First

The museum's insight about "the how and why of things being imagined, planned, drawn, produced, materialised, accepted, perceived and consumed" reveals something crucial: imagination comes first in the sequence. Before we can build responsibly, we must imagine responsibly.

In our AI moment, this is both our greatest opportunity and our greatest risk. When imagination is democratized, when anyone can prompt a model to generate code, content, or analysis, the quality of our imagination becomes the determining factor. The museum's provocative questions apply directly: "Do we really need so many things to live our lives? What meaning should be given to new things? Do we even need new things?"

Replace "things" with "AI applications" and the urgency becomes clear. Do we need another chatbot, another content generator, another automation tool? Or should we be imagining software that genuinely elevates human capability while respecting planetary boundaries?Givenchy/Alexander McQueen Dress and cape 1997, Jean Paul Gaultier Jumper 1997

Five Threads Through Time

Across 120 years, the exhibition reveals objects as mirrors of collective questions. Five leitmotifs run through every room, as relevant to today's AI builders as they were to yesterday's furniture makers:

Purpose: Why should this exist? The progression from Belle Époque prestige objects to today's survival-focused, circular design reveals changing answers to fundamental questions of value.

Material & Technique: What new medium is available and how do we tame it? Each era grapples with its transformative material: steel, plastic, digital bits, and the social implications of new capabilities.

Politics & Power: Who controls the narrative? From World Fair nationalism to Estado Novo propaganda to brand cults, every "thing" embeds someone's vision of how society should work.

Consumption & Identity: How do "things" say who I am? The evolution from luxury Art Deco to postmodern excess to DIY counter-culture shows how objects become identity markers.

Responsibility: What debt do we owe the planet and society? The arc from early craft revivals through the anti-design movement to today's reuse/recycle/repair ethos reveals growing consciousness of consequence.

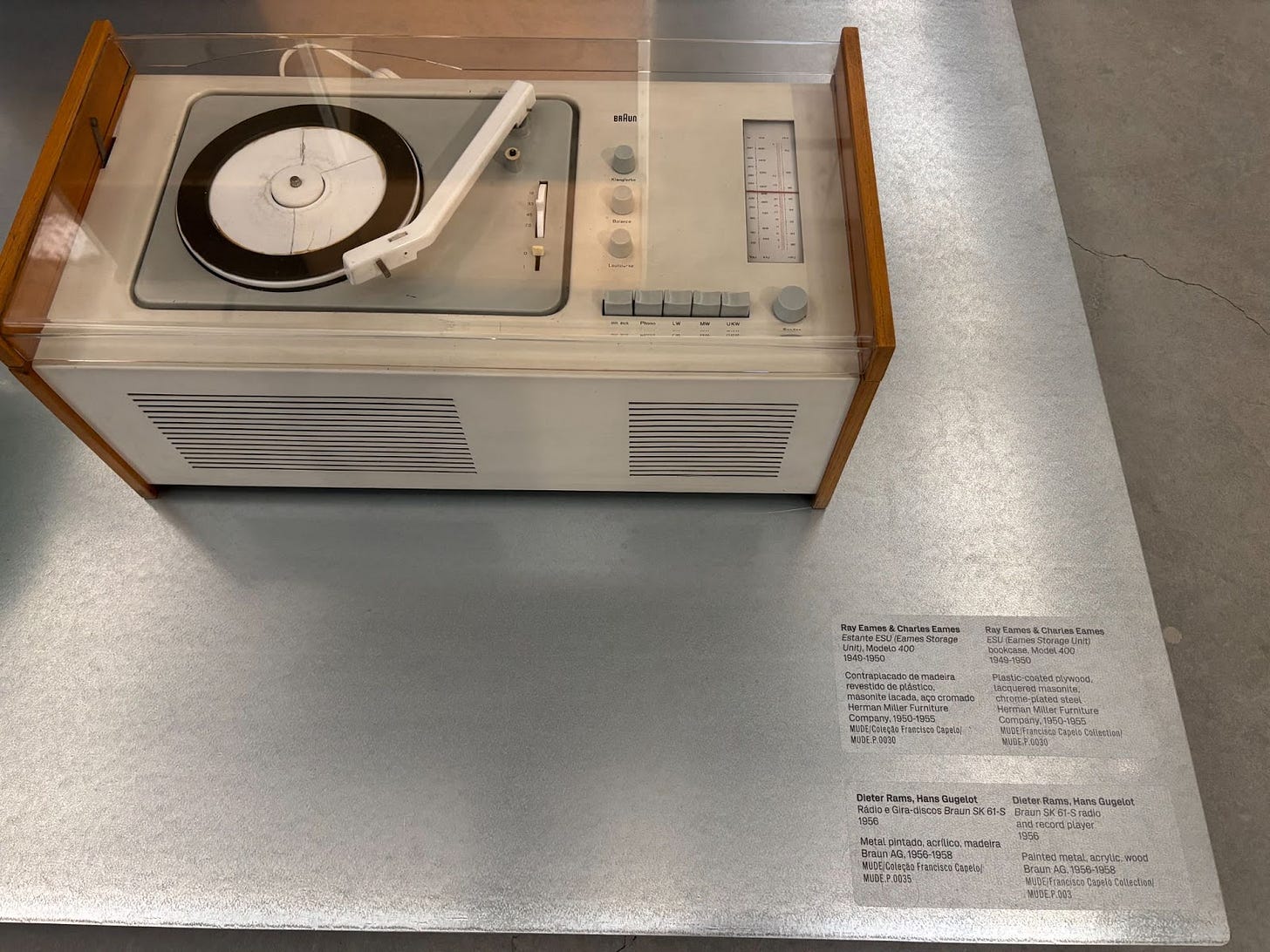

Dieter Rams, Hans Gugelot Braun SK 61-S radio and record player 1956

The Rhythm of Technological Transformation

What struck me most was the predictable rhythm each transformative technology follows:

1900s: Optimistic Display

The Belle Époque mentality: "Exhibit modern identity abroad." Portugal's Universal Exhibition pavilion embodied confident nationalism. A Paródia newspaper caricatures mocked tradition while celebrating progress. The question was simple: how do we show the world we've arrived?

AI parallel: Today's AI demos and capabilities showcases. We're still in the "look what's possible" phase, focused on impressing rather than integrating.

1920s-30s: Democratizing Function

"Do more with less" became the modernist rallying cry. Buckminster Fuller's cantilever seats and Bauhaus-influenced chairs promised democracy through rational design. The belief: good design could be mass-produced affordably, making quality accessible to all.

AI parallel: The promise that large language models will democratize sophisticated reasoning, that no-code AI will make programming accessible to everyone. Same utopian energy, same faith in technology as social leveler.

1930s-50s: Appropriation and Propaganda

The Portuguese Estado Novo's "Good Taste Campaign" showed how authoritarian regimes co-opt modernist aesthetics. Traditional craft vocabulary was pressed into nationalist propaganda. Clean lines became tools of control.

AI parallel: This is our current inflection point. Who controls the training data? Whose values get "aligned"? When AI systems scale to billions of users, what assumptions are we baking in? The same aesthetic neutrality that made modernist design appealing to dictators makes AI systems attractive to would-be controllers of information.

1945-60s: Reconstruction and Mass Hope

Post-war optimism channeled into "Good Design",durable, affordable objects for everyone. The Vespa scooter, Eames furniture, and the Isetta microcar embodied democratic access to mobility and comfort. Function met mass production.

AI parallel: We're entering this phase now. AI-powered tools for education, healthcare, creative work,the practical applications that could genuinely improve quality of life at scale.

1960s-70s: Miracle Materials and Growing Doubt

Alain Resnais' Le Chant du Styrène celebrated plastic's "resistance, versatility, plasticity, lightness, durability, and low cost." But Victor Papanek simultaneously pioneered social design, critiquing consumerism and calling for environmental responsibility. Plastic went from miracle to menace in a single decade.

AI parallel: We're living through this same inflection point. Compute abundance mirrors plastic's early hype, but energy costs and e-waste concerns are mounting. The initial euphoria over AI capabilities is giving way to questions about environmental impact, labor displacement, and whether we're solving real problems.

1980s-90s: The Designer Superstar Era

Gilles Lipovetsky's "Era of Emptiness": utilitarian objects became status symbols, design became pure surface. Alessandro Mendini's "Proust" armchair exemplified postmodern excess, function divorced from form, meaning from utility.

AI parallel: When every startup can access frontier model capabilities, differentiation moves toward branding and artificial scarcity. We see AI companies creating "designer" models and cult-like followings around commodity capabilities. The risk of AI becoming about lifestyle brands rather than substance.

1990s-2020s: Planetary Consciousness

The return to purpose. "Reuse-Recycle-Repair" flat-pack furniture, bio-inspired textiles, nomadic home goods designed for a climate-conscious, digitally networked world. Traditional crafts gained new relevance as ecological practices proved valuable "in the context of the current environmental emergency."

AI parallel: This is where we need to go,and where the most thoughtful builders are already heading. After the initial AI hype cycle, there's growing appreciation for craft, for deep architectural thinking, for systems that consider their full impact.

Victor Palla & Bento d’Almeida Room Divider 1956

Curating the Next Room: "What Are Models For?" (2020-2050)

Standing in the museum's final room, I imagined the exhibit labels that future curators might write about our era:

"Intent Compiler" Workstation (2024) Voice-to-software pipeline translating a startup's spec into running backend; celebrated for "designing the invisible."

"Carbon-Miser" Language Model Card (2027) First foundation model to publish a live energy dashboard and auto-throttle itself to stay within a user-set footprint.

"Reposcope" Circular-AI Repository (2029) Open platform where discarded model checkpoints are mined, remixed and redeployed,turning 'waste compute' into raw material.

"Commons Contract" Wallet (2032) Cryptographic wallet that tracks data-set lineage and pays micro-royalties to original contributors when derivatives are commercialized.

These aren't science fiction, they're extrapolations of patterns the museum revealed. Every era eventually develops resource consciousness, circular practices, and tools that honor the full lifecycle of creation.

Thomaz de Mello Bedroom furniture; dressing table 1942

The Five Questions for AI Builders

MUDE's leitmotifs translate directly into questions every AI company should ask:

Purpose: What human capability are we genuinely enhancing? Why should this model exist rather than a simpler alternative?

Material & Technique: How do we treat compute, data, and human attention as the finite resources they are?

Politics & Power: Whose worldview are we encoding? Who benefits from our choices about training data, safety measures, and access models?

Consumption & Identity: Are we creating tools that help people think better, or status objects that signal belonging to an AI-native tribe?

Responsibility: What are the second and third-order effects of deploying this capability at scale?

MUDE Museum Design Lisboa 2025

The Museum's Answer

Walking back into Lisbon's afternoon light, I understood why this exhibition moved me so deeply. Every transformative technology goes through the same cycle: utopian promise, widespread adoption, unintended consequences, excess and reaction, and finally, if we're fortunate, wisdom.

The most beautiful objects in the exhibition weren't the most technically innovative or aesthetically striking. They were the ones where you could sense the maker's deep consideration of human needs within material and social constraints. A chair that perfectly supports the human form using minimal steel. A poster that communicates with clarity while respecting the viewer's intelligence. A system that hides complexity while enabling capability.

The museum's answer to "What are things for?" is clear: they're for serving human flourishing, but only when their creators have deeply considered purpose, context, and consequence.

MUDE's curatorial statement reveals its deeper ambition: "The museological intention to provoke discussion on current development models and the urgency of economic slowdown. The vision put forward by the MUDE – Design Museum, more than merely encouraging debate on the changes needed, seeks to position MUDE as a driving force in making them happen."

This is exactly what we need now in AI: not more parameters or faster inference, but deeper consideration of what we're building and why. We need to become driving forces for imagining beautiful software, systems that are thoughtfully architected, elegantly designed, and worth the resources they consume. The question "What are things for?" should hang in every startup office, every research lab, every design review.

Because 120 years of design history suggests that technologies become truly beautiful, and truly lasting, only when their creators grapple seriously with all five leitmotifs. When they ask not just "can we build this?" but "what is this for, who does it serve, and what world does it help create?"

The choice is still ours to make. But the museum's survey suggests we'd better choose with the same intentional craftsmanship that has always distinguished lasting design from mere novelty.

Our era's fingerprint will be intent-shaping, self-aware, resource-sober AI systems, immaterial in form yet deeply material in impact. Let's curate them with the same courage, craft, and conscience that past designers applied to steel, plastic, and wood.

More essays: Founder Mental Software, Normalizing the Founder Journey, Agentic systems: panning for gold, AI Engineer World’s Fair 2025 - Field Notes